I’m a West Ham fan. Our stadium is not good. It’s beautiful, but broken. It hosted the greatest British sporting event of the last 50 years, a grand and gleaming Olympic Games, but cannot handle a lower-mid-table Premier League game. This half-a-billion pound stadium gleams in the sunlight, but it’s full of holes, gaps, missing pieces, large canyons between prefab stands that are papered over, almost literally, with plastic claret sheets. The stadium’s problems are not just physical; they’re also psychological. It doesn’t feel like a football ground because it’s not one. It makes you wonder: what makes a great football stadium?

Grounds grow to match the identity of their team. Character is more important than capacity or having a technologically advanced concourse. You know it when you see it – or feel it: this sense that you are tied only to geography but to history. “Liverpool are one of those clubs who have a really strong identity,” says Professor Murray Fraser of the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. “When you go to Anfield, it very obviously is the ‘church’ of that community around it. I found it quite astonishing when I first went there and saw the houses around it. The people who live in that area see the stadium every day, get to look at Anfield every day as they move around town, and that builds a huge sense of identity.”

There are plenty of grounds that inspire similar feelings of civic pride and awe. Sat bang in the middle of Burnley, Turf Moor feels hard worn and hard-won, its dressing rooms spare and its away seats wooden, typical of a team that have dragged themselves up from the lower reaches of the league. Thirty miles south, Manchester United’s giant Old Trafford still feels like it’s part of the community, lined with red-brick houses up Sir Matt Busby Way, a giant club famous for both its general bigness and its long-held reliance on local talent.

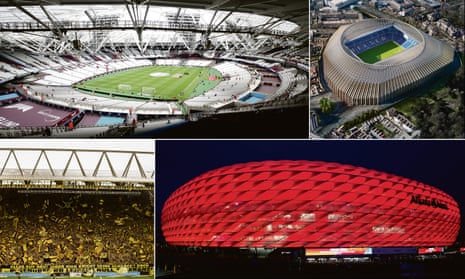

There is Celtic Park’s studied continentalism and Ibrox’s almost parodic Britishness. Dortmund’s legendary Yellow Wall stretches up into the sky and bears down on opposing teams as they attack the goal. At Boca’s La Bombonera, a D-shaped ground with a sweeping half-bowl and a single flat stand, the noise resounds from the curve and reverberates off the opposite stand, evoking a concert hall more than a ground, which is fitting for a team more known for its thrilling atmosphere than its football.

It is easy to write off new stadiums as just physical manifestations of what is wrong with the game today, with every bell and whistle an affront to the charm and reality of the game we love. But these grounds grow and mutate as the game does, changing with the larger culture and community of an area, although there does need to be something real for fans to hold on to.

“When it comes to the design process,” says architect Christopher Lee. “It is about understanding what the DNA of a club is, what their supporters are about and what the nuances and traditions are – whether that’s in east London or northern Mexico.” Lee has worked on the Emirates Stadium, the Millennium Stadium (with Europe’s first moving roof), and has been at the heart of Tottenham Hotspur’s new ground.

“Identity is really important and sometimes that can be lost,” he says. “Which is why, with the new Tottenham stadium, we’ve been looking at how you break it down: people will have come to the new ground who used to sit in the South Stand or the North Stand, with the constant, chanting games that went on between the two, and that’s led us to a little bit of an evolution from creating engineering-driven seating bowls to try and create more of a genuine identity. Until quite recently, in the seventies and eighties, there was basically no such thing as ‘stadium architecture’. It was an engineering pursuit and it was seen as an engineering activity – and the builders were guys who tend to build bridges. It was a very pragmatic approach.”

Pragmatism no longer cuts it. Great stadiums have to resonate with the local community. Where the stadium sits in the city can make or break a ground: there is the London Stadium, situated oh-so-pragmatically in the middle of a park away from residents thanks to security measures put in place during the Olympics, and the old Juventus ground, the Stadio delle Alpi, surely one of the worst stadiums a club of that size has ever had.

The never-used athletics track, terrible sightlines and a location way outside Turin did not inspire fans. The 67,000-seater ground was regularly left only a third full. For one Coppa Italia game against Sampdoria in 2001-02, only 237 supporters showed up. It was demolished in 2008, just 18 unloved years after it opened.

Estádio Municipal de Braga in northwestern Portugal is carved from granite in the face of Monte Castro, with two beautiful lateral stands, rock behind one goal looming like a kop and the city sprawl of Braga behind the other. Bari’s Stadio San Nicola is a stripped-back tribute to the classic amphitheatre. Considered something of a classic, with its construction made of 26 concrete “petals”, the stadium is unlike many of the overbearing grounds in Serie A; the structure feels delicate and airy, with fans sat around its uppermost tiers, making the most of the sunshine on the coast of the Adriatic sea.

Then there’s the Allianz in Munich. Designed by renowned Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, its central concept was clear. The idea of strength and robustness mixed with eye-catching flair has defined the team, so the stadium was constructed from concrete and steel latticework, and the building’s facade is wrapped in illuminated air cushions that change colour to reflect the two teams playing inside.

“It’s a very simple idea that acts as an urban marker,” says Murray of the Allianz. “If Bari’s design was the amphitheatre and its simplicity, Bayern’s is the reimagining of the cathedral: the grand physical form as part of the city. I think the most successful stadiums are the ones that approach architectural forms with real clarity. You need to decide what kind of ground you want to create and then follow that.”

Herzog & de Meuron’s proposed design for Chelsea’s next stadium also takes a central theme and pursues it clearly. Surrounded by 264 sculptural brick pillars, it “will have a lightness of expression when viewed directly but also a solidity and textural materiality when seen obliquely,” according to the firm. The design takes a London material – brick – and treats it as a spectacle.

These stadiums of the near future will not be to everyone’s liking. For every fan who marvels at contemporary design, there is another who wants to return to the good old days, splintered arses and all. “Nostalgia is currency in football,” says Owen Pritchard, former editor of design bible It’s Nice That. “The era of a meat pie and a cup of Bovril will be gone for good before too long. To a certain extent, so it should be. Football tickets are expensive. You’d be pissed off if you paid upwards of forty quid to sit behind a post in a creaky stadium. There’s a romance about the days of yore in football but, quite frankly, people sometimes forget it was fucking dangerous.”

Nostalgia is warm and cosy, a blanket. We can fuss, obsess and mythologise every part of the past because we know it can’t come back to bite us. Our nostalgia for stadiums is often the same: the Boleyn Ground was perfect, old Wembley – the dog track with a football ground in the middle – was perfect. They say don’t meet your heroes. You can’t, anymore, because they’ve all been knocked down. It’s safer this way. But having that through-line of nostalgia in new stadiums is important: something that connects you to the past – warped and mythologised though that past may be – is essential. When Arsenal proposed a move from Highbury to the Emirates, carrying that sense of tradition across proved a challenge for architects.

“Arsenal had been at Highbury since 1908,” says Lee. “It was a much-loved stadium, a beautiful stadium, designed by Archibald Leitch, and the East Stand was grade one-listed art deco. As a local resident, it was my local team, and it was an incredible building to try and deal with. We spent a long time with the club trying to change and expand it until, finally, and slightly sadly, realised that we would have to leave Highbury to design what is now the Emirates.

“One school of thought was: ‘OK, we’ll just replicate some art deco in the interior and that will be the DNA carried over, a sort of pastiche version’. But really what we developed was the idea of trying to distil an air of permanence and longevity. It was all about creating with materials that would last as long as Highbury and get better over time. We invested a lot of time and a lot of money in creating a building which was going to be there for the next hundred years. Fans really latched on to the idea: it wasn’t going to be this thin building metal that would age and look crap in 20 years. It will just look better. When you go there now, and you see the wear and hand marks in materials like the brass in some of the Club levels and the director’s boxes, you get that idea of permanence and longevity coming through. That’s what the club wanted, that was at their roots.”

The Emirates has faced some criticism – I once heard someone call it a stadium for people who go to the London Coffee Festival – but that could be down to the fans not enjoying what’s happened on the pitch. At least it’s a bespoke football stadium that is, ostensibly, just for them.

National stadiums can be difficult. So it has proved for England, where there is little sense of national identity and games at Wembley are seen as fodder for daytrippers. The mythologising around the new Wembley has often felt artificial, with lots of marketing spiel but very little tradition to experience. It is one of the most famous stadiums in the world, yet visiting Wembley has always felt like a chore.

“The Millennium Stadium – or whatever it is called right now – absolutely nailed it,” says Pritchard. “It’s smack bang in the middle of Cardiff, opposite the train station and on matchday the whole city is bouncing. The roads are shut and everything is geared towards the game. You just can’t miss it; it owns the city. And once inside, the tight site means that the seating is steep and the fans are right on top of the action. There’s not a bad seat in the house. But compare that to Wembley. It’s a pain in the arse to get to and once there, the atmosphere is paper thin. The bowl is too shallow; the whole thing is too slick.”

Instinctive footballers are said to struggle when given too much time to think and perhaps the new Wembley had too much space to play with. With too many ideas stuffed into one building, the purity of the vision was lost. “Wembley Stadium is a business park,” says Murray. “It operates on a kind of model – the density of rooms in the ground, the facilities and conference room, etc – to ensure it makes money. But when you look at it, it just swaddles – all these extra elements makes it feel really puffy and neutralised. The experience of going to the stadium has been lost.”

“The FA calls it ‘the Home of Football’, but it’s not,” adds Pritchard. “It looks like a shopping basket and it’s in Brent.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion