The first question of the press conference was about Petr Cech. The veteran Arsenal goalkeeper had just announced his retirement from football at the end of the season, and as Unai Emery was asked to offer some words of tribute you could see the cogs whirring in his head as he composed his response. A short pause. “Good afternoon,” he began with his customary courtesy. “First, I think he’s a very big person.”

Certainly there could be no qualms about the factual content of the statement, given Cech’s height of 6ft 5in. Yet the suspicion remained that this was not quite the glowing tribute to his outgoing stalwart that Arsenal’s manager had quite intended. And as Emery departs north London, the suspicion remains that it is little comic vignettes like this – as much as anything he achieved on the pitch – that will be the true legacy of his time at Arsenal.

Let’s be clear about one thing from the outset: Emery didn’t lose his job at Arsenal because of his language skills. Failure has a nasty habit of amplifying a man’s traits into flaws, and had Arsenal qualified for the Champions League or made a stronger start this season, Emery’s arresting linguistic salad would have been the least of anybody’s concerns.

There were also times, to be fair, when the parody of Emery’s English verged on unkindness. It was ultimately to his credit that he tried, even though by his own admission his level was mixed. And if the results occasionally felt as if he was running his own speech through a sort of real-time Google Translate, it takes a certain conviction to eschew the translator and face the cameras in your third language. As Tennyson almost wrote, perhaps ‘tis better to have spoken and garbled than never to have spoken at all.

Yet as results began to dive, it clearly became an issue: not just in the media but, by all accounts, in the dressing room too. The fact he was perfectly capable of great eloquence in his Spanish-language interviews hardly helped matters. Nor did having to follow Arsène Wenger, perhaps the most articulate foreign manager ever to have worked in the English game. The contrast between “I believe the target of anything in life should be to do it so well that it becomes an art” and “All the people who work here, I think they help us for all the work” was always going to jar slightly.

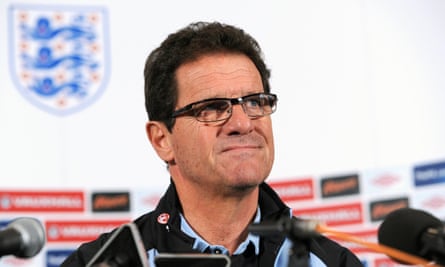

Perhaps there are wider traits at work here, too. Emery is by no means the first manager to arrive on these shores and have problems with the language. But whereas the struggles of Claudio Ranieri, Juande Ramos and Fabio Capello were regarded as surmountable obstacles – even quaint affectations – Emery’s are somehow regarded as symptomatic of a wider failure. The real lesson here, for Emery and others, is the way that communication – always an essential part of the manager’s armoury – is becoming, in many ways, the very point of the job.

Back in those giddy early days, as the first overseas managers began to plant their flags like pilgrims, there was a certain bemusing fascination to the armies of translators and misunderstandings they brought with them. How we chuckled when Ossie Ardiles pronounced it “Tottingham”, or when Capello referred to the former Milan players “Rye Wilkins” and “Mark Hatley” during his first press conference as England manager.

By the current decade our patience for foreigners butchering the Queen’s had clearly begun to wear thin. Despite speaking excellent English, André Villas-Boas was roundly ridiculed for his eclectic turns of phrase: Michael Dawson being “a player of immense human dimension” or Jermain Defoe being able to “smell every cross”. In his autobiography, the former Burnley chief executive Paul Fletcher openly scoffed at Villas-Boas’s language skills when he came to interview for a job. “Would Burnley players have understood ‘solidificate’, or some of his other terms?” Fletcher wrote. To which the answer is: um, probably yes.

Now, it seems, we’ve come full circle. In an age where clubs are as much made-for-television entertainment vehicles as sporting enterprises, the role of the coach has subtly shifted. Once primarily a behind-the-scenes job, the modern Premier League coach is essentially that of a televangelist. The league position is now largely determined by wage bill, recruitment by the transfer committee, contract negotiations by the board, style of play by the sporting director. The coach’s primary function is thus to tell a story compelling enough that everyone – dressing room, owners, broadcasters and fans – will jump on for the ride.

The leading managers in the game – Guardiola, Klopp, Pochettino, Mourinho – recognise this instinctively. Under these new rules, language is no longer an option but a weapon to be used with all due precision and nuance. It is why Diego Simeone will probably never manage in England, why the stock of quieter, less loquacious managers David Moyes and Mark Hughes has never been lower.

There is a story about Moyes from his time at Manchester United, when in order to help him prepare for an upcoming press conference, the club’s media team prepared him a sheet of likely questions he might receive. Moyes studied it intently, turned it over, and then with a mixture of incredulity and apoplexy blurted out: “But where’s the answers?”

This, essentially, is where Emery erred. His mistake, above all, was to believe that his work would do his talking for him. Ultimately, however, his failure to articulate a coherent identity for Arsenal, to sell himself and his methods, his refusal to feed the dream machine, would hasten his downfall. After all: there’s little point in being able to speak a language if you have nothing to say in it.