White Hart Lane station, 8.20pm, the Sunday before last. The north London derby has finished a couple of hours earlier, Arsenal winning 2-0, and a lone Tottenham fan starts to sing. The man, in his mid-to late-50s, wants it to be known that everyone will be “having a party when Sol Campbell dies”. The platform is not particularly crowded and nobody else joins in. Equally, no one steps in. The train arrives, the man gets on and goes home.

In the seconds before kick-off, there had been a different chant from the Spurs support in the South Stand. This time, it comes from hundreds of them and is similarly vile. It is drowned out by the roar for the start of the game and everybody’s focus shifts.

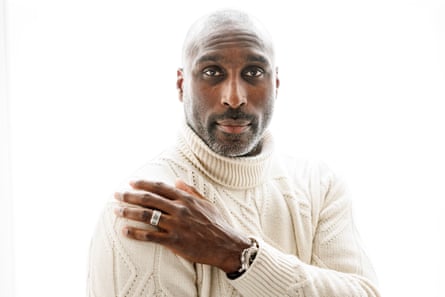

Campbell pauses. He does this a lot over the course of a traumatic and triggering interview, trying to process, trying to find the right words. The abuse of him remains part of the Spurs match-day experience; home and away, in and around the stadiums. Anti-Campbell sentiment was heard at the club’s next two matches – at Manchester City and Fulham.

It is not sung by everyone and it is not always easy to pick out inside the grounds. Nor does it happen every time. But it is often there, an almost incidental detail. Up the Spurs. And up yours, Sol Campbell; those that sing doing so because this is what they do, not all of them stopping to think about the barbaric content.

“It’s almost as though people have forgotten how to be human,” Campbell says. “Wishing and hoping that someone is going to die? And you’re going to be having a party? What world are we living in? I know football has its tribalism but if no one around feels that this is unacceptable … well, we’re in a really sorry place.”

Campbell made his Bosman move from Spurs to Arsenal in 2001, meaning that some of his tormentors were too young to be aware of what he had done at the time – the depth of the betrayal by a homegrown hero – or maybe not even alive. The hatred has been passed down.

Campbell wants to strike the right tone as he speaks publicly about the subject for what he hopes can be the final time. It could be that he is the most reviled British footballer ever in the eyes of one set of fans. The emotional toll has been immense, taking in a psychological breakdown in 2006 and many other moments when he has felt hunted and overwhelmed.

What it comes down to for Campbell is basic humanity. He is no longer the 26-year-old who crossed the divide, all headstrong confidence, flushed with the belief that he could take on anything. Rather he is a worldly 48-year-old, a married man with children, for whom he seeks a compassionate society. After all these years and with so many bad things across Europe and beyond – from health emergencies to economic crises to war – do we really still need to be doing this?

“It’s as though I’ve become a caricature, that I’m not a human being any more,” Campbell says. “It’s like some folklore song, people around the campfire, passing on the stories from old to young. ‘Let’s talk about this, let’s sing about this.’

“We are talking about nearly a quarter of a century [since the transfer]. Where are we going as human beings if someone cannot move on? I don’t think people realise how hurtful the hate and vitriol is to me. I get the situation but it’s been such a long time.”

Campbell retired as a player in 2011 – one year after he married Fiona Barratt, an interior designer. They have three children together and Isabella, 11, Ethan, nine, and Georgiana, seven, are at ages where Campbell worries about the potential for them to be affected by the treatment of him, the perceptions of him.

Isabella and Ethan are promising tennis players and Campbell even talks about them “making it” in the sport. He visibly relaxes when he discusses them and Georgiana and, for a few minutes, he is just another dad with dreams and so much love. But then the conversation switches to whether he has taken them to any football matches.

“No, never,” Campbell says. “It’s just the culture around the game. You want to protect them and you never know. I don’t want to go to a match and have someone who is not a fan of that particular club suddenly say something for no reason.”

What does Fiona think of it all? “She is disgusted,” Campbell replies. “And as a white woman and with the majority of people who are doing it being white men and boys … it’s quite scary. Fiona is a wonderful, wonderful woman and a brilliant mother. That’s the only way I can describe her. Just beautiful in every single way.”

Campbell can pinpoint the moment when he hardened as a person – out of necessity, survival instinct. White Hart Lane stadium, 17 November 2001, his first derby in the incendiary red of Arsenal. Campbell always had a quiet determination, a single-mindedness to make the most of his talents. Now he doubled down on everything. Ferociously.

“It was an inferno of hatred that day,” Campbell says. “There were bricks at the coach, a burning effigy of me and everybody accepted it, even the good people that were around. ‘Oh, Sol’s big. He can take it.’

“I had to go deep inside myself and I changed. I had to learn in 90 minutes how to deal with those things and how to play a football game. I had to fight a mental battle and I said to myself: ‘I’m just going to win.’ As a football player in a fantastic team, that’s all I could do. But I can’t do that now. I can’t back myself up on the pitch.”

Campbell was shaped by his upbringing in the east London neighbourhood of Plaistow. The youngest of 12 siblings (nine brothers, two sisters), he faced a battle to be heard and so he internalised things. He would sometimes be described as a closed person during his career; the public did not know him and that led to misconceptions. What he was perfectly clear about was his desire to get to the top.

“I’m from such a poor family, a tough-as-anything area and I’d seen so many people around me fail, so much heartache,” Campbell says. “I wasn’t going to allow that to happen to me. I was completely focused on football. I didn’t have time to mess around.

after newsletter promotion

“I was a boy that started a pension at 17. What kind of boy does that?! But what’s wrong with being a boy who doesn’t have much and what he gets, he makes sure is utilised properly? Because he never knows whether it might be taken away. I am from a background where things get taken away.”

Campbell’s success at Arsenal only made things worse with the Spurs support, particularly when he was a part of the “Invincibles” team in 2003-04 that clinched the title at White Hart Lane. The abuse remained a constant and it was a contributing factor to his breakdown.

Campbell had lost his father, he was struggling for form and fitness and everything got on top of him during Arsenal’s home match against West Ham in February 2006. He walked out of Highbury at half-time and the next day he headed to Brussels in an attempt to clear his head.

“I thought that was it,” Campbell says. “It was finished. I couldn’t take any more. Playing good football was the only thing that was holding me together and I was losing that. It was like a house of cards.”

What is striking when Campbell looks back on the episode is how, broadly, he had to deal with it alone. There was no sports psychologist for him. He simply spent a few nights in Brussels – “I had a friend there and she helped me out” – reported back to Arsenal, where Arsène Wenger asked him to give a speech to the rest of the squad, containing an apology, and cracked on. By the end of the season, Campbell was playing and scoring in Arsenal’s Champions League final defeat against Barcelona.

Was there a nadir in terms of the abuse? Probably in September 2008, Campbell says, when he was playing for Portsmouth and they welcomed Spurs to Fratton Park. He was moved to make a complaint to the police and they would bring charges against 11 people for “indecent chanting”. Three of them were under the age of 15. The chants that were read out in court included the lines: “We don’t give a fuck if you’re hanging from a tree, You Judas cunt with HIV.” Others featured the repetition of the words “gay boy”.

Campbell tells a more recent story from the summer of 2021 when he was in Rome as a TalkSport pundit for England’s European Championship quarter-final against Ukraine. He and his colleagues were having lunch at a restaurant when a man started to hurl abuse at him.

“He was English, with his girlfriend and he couldn’t have been more than 25,” Campbell says. “It was ‘Judas’ and … blah, blah, blah. He filmed it because he thought I was going to do something. I didn’t do anything. Sometimes I do think: ‘Am I going to bump into someone who is going to shout rubbish at me?’ It’s got a lot less, don’t get me wrong. But I still get randoms … taxi drivers, builders or whatever. It happens. Of course, it does.”

Campbell’s “caricature” line resonates because it feels as if his achievements on the pitch – the trophies, the 73 England caps, the six major tournaments in a row, the period immediately after his move to Arsenal when he was possibly the best centre-half in the world – are being obscured.

Ditto his personality and the work he has done as a community leader; helping underprivileged children, for example, or collaborating on the opening of the Black Cultural Archives Museum. There is no doubt that the cloud over Campbell has held him back in terms of job opportunities, including those in football management.

And so it comes down to this. Campbell pauses. Then the words tumble out. “I was a young boy when I signed for Arsenal,” he says. “I didn’t have a family. It’s a different story if I had kids. I might have thought differently. I don’t know. Maybe if I was 30 or 35, I’d have thought differently. But I was 26.

“That’s not me now. Who stays the same every year or over every five years … let alone 22 years? I’m not 48 making that decision. For me, it’s a plea. I want a clean slate. Look into your hearts, look into your souls and give me a clean slate. Take me out of the caricature and see me as a human being.”